As every third-grader knows, Thomas Edison invented the electric light bulb.Or did he?

It’s painful to cast aspersions on the reputation of one of America’s heroes, but Edison, who patented his bulb in 1879, merely improved on a design that British inventor Joseph Swan had patented 10 years earlier

The story of the light bulb begins long before Edison patented the first commercially successful bulb in 1879. In 1800, Italian inventor Alessandro Volta developed the first practical method of generating electricity, the voltaic pile. Made of alternating discs of zinc and copper - interspersed with layers of cardboards soaked in salt water - the pile conducted electricity when a copper wire was connected at either end. While actually a predecessor of the modern battery, Volta's glowing copper wire is also considered to be one of the earliest manifestations of incandescent lighting.

Not long after Volta presented his discovery of a continuous source of electricity to the Royal Society in London, an English inventor named Humphrey Davy produced the world's first electric lamp by connecting voltaic piles to charcoal electrodes. Davy's 1802 invention was known as an electric arc lamp, named for the bright arc of light emitted between its two carbon rods.

While Davy's arc lamp was certainly an improvement on Volta's stand-alone piles, it still wasn't a very practical source of lighting. This rudimentary lamp burned out quickly and was much too bright for use in a home or workspace. But the principles behind Davy's arc light were used throughout the 1800s in the development of many other electric lamps and bulbs.

In 1840, British scientist Warren de la Rue developed an efficiently designed light bulb using a coiled platinum filament in place of copper, but the high cost of platinum kept the bulb from becoming a commercial success. And in 1848, Englishman William Staite improved the longevity of conventional arc lamps by developing a clockwork mechanism that regulated the movement of the lamps' quick-to-erode carbon rods. But the cost of the batteries used to power Staite's lamps put a damper on the inventor's commercial ventures.

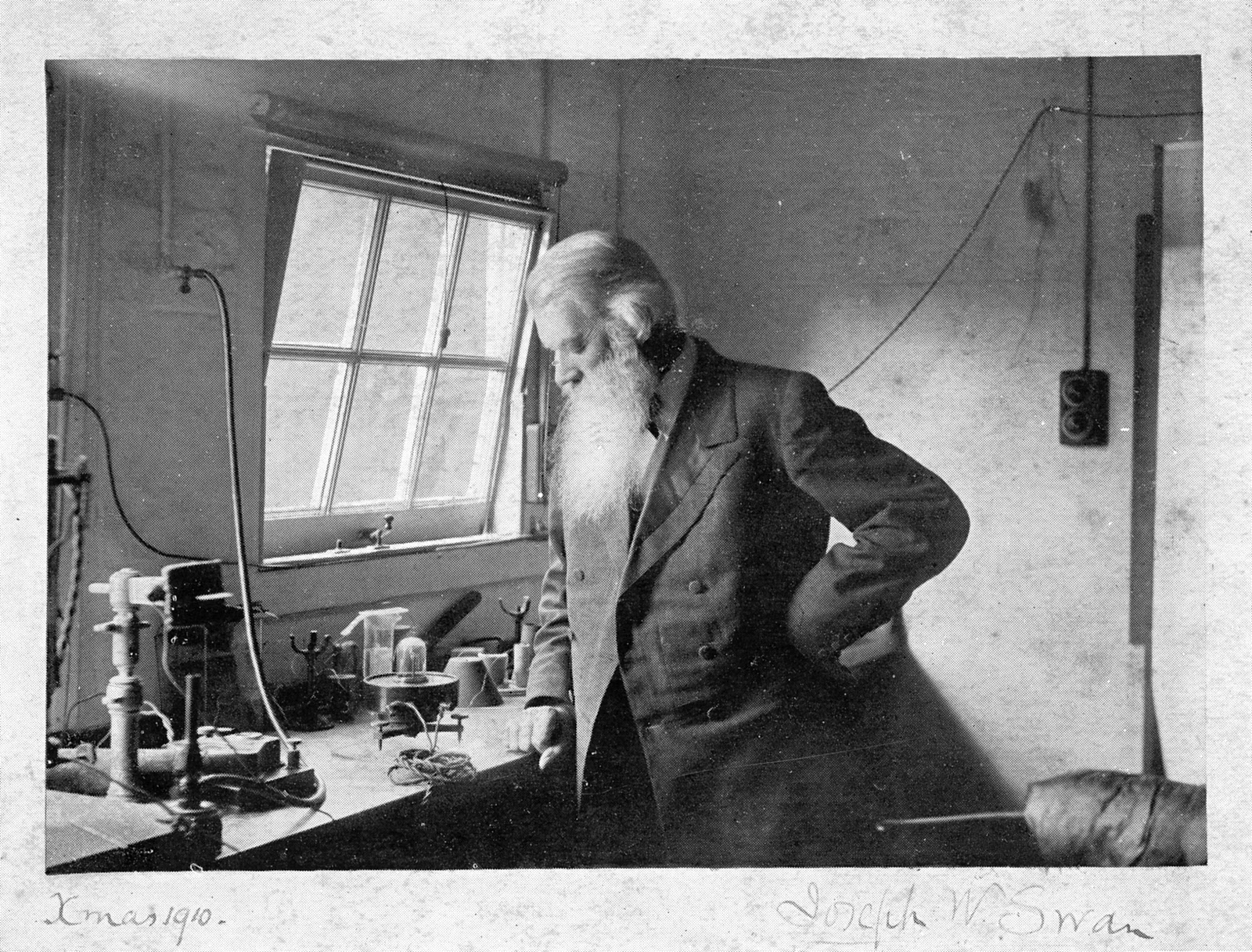

Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, was a British physicist and chemist. He is known as an independent early developer of a successful incandescent light bulb and is the person responsible for developing and supplying the electric lights used in the world's first homes and public buildings (Savoy Theatre in 1881) to be lit with electric light bulbs

In 1904 Swan was knighted by King Edward VII, awarded the Royal Society's Hughes Medal, and was made an honorary member of the Pharmaceutical Society. He had received the highest decoration in France, the Légion d'honneur, when he visited an international exhibition in Paris in 1881. The exhibition included exhibits of his inventions, and the city was lit with his electric lighting. Swan was the maternal grandfather of Christopher Morcom, Alan Turing's close friend and first love during their studies at the Sherborne boarding school.

In 1850, English chemist Joseph Swan solved the cost-effectiveness problem of previous inventors by developing a light bulb that used carbonized paper filaments in place of ones made of platinum. Like earlier renditions of the light bulb, Swan's filaments were placed in a vacuum tube to minimize their exposure to oxygen, extending their lifespan. Unfortunately for Swan, the vacuum pumps of his day were not efficient as they are now, and his first prototype for a cost-effective bulb never went to market.

While Swan waited for the development of quality vacuum pumps, an American inventor, Charles Francis Brush, was busy developing an electric arc lighting system that would eventually be adopted throughout the United States and Europe during the 1880s. While not truly a light bulb, Brush's lighting systems could be used wherever bright lights were needed — such as in streetlights and inside commercial buildings. To power his systems, Brush developed dynamos - or electric generators - similar to those used that would one day be used to power Edison's electric lamps.

In 1874, Canadian inventors Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans filed a patent for an electric lamp with different-sized carbon rods held between electrodes in a glass cylinder filled with nitrogen. The pair tried, unsuccessfully, to commercialize their lamps but eventually sold their patent to Edison in 1879.

Swan sued Edison for patent infringement, and the British courts ruled against Edison (as punishment, Edison had to make Swan a partner in his electric company). Even the U.S. Patent Office decided in 1883 that Edison’s patent was invalid, as it also duplicated the work of another American inventor.

As it happens, Swan and Edison worked from bulb designs that had been in use since the early 1800s. The general principle was, and still is, this: When electrical current flows through the bulb’s filament, the filament heats up and glows, which produces light. The inside of the bulb is a vacuum, hence oxygen-free, so the filament doesn’t get oxidized and the glow lasts a long time.

In 1850 Swan began working on a light bulb using carbonized paper filaments in an evacuated glass bulb. By 1860 he was able to demonstrate a working device, and obtained a British patent covering a partial vacuum, carbon filament incandescent lamp.[citation needed] However, the lack of a good vacuum and an adequate electric source resulted in an inefficient light bulb with a short lifetime.

In 1875 Swan returned to consider the problem of the light bulb with the aid of a better vacuum and a carbonized thread as a filament. The most significant feature of Swan's improved lamp was that there was little residual oxygen in the vacuum tube to ignite the filament, thus allowing the filament to glow almost white-hot without catching fire. However, his filament had low resistance, thus needing heavy copper wires to supply it.

Swan first publicly demonstrated his incandescent carbon lamp at a lecture for the Newcastle upon Tyne Chemical Society on 18 December 1878. However, after burning with a bright light for some minutes in his laboratory, the lamp broke down due to excessive current. On 17 January 1879 this lecture was successfully repeated with the lamp shown in actual operation; Swan had solved the problem of incandescent electric lighting by means of a vacuum lamp. On 3 February 1879 he publicly demonstrated a working lamp to an audience of over seven hundred people in the lecture theatre of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne, Sir William Armstrong presiding. Swan turned his attention to producing a better carbon filament and the means of attaching its ends. He devised a method of treating cotton to produce "parchment used thread" and obtained British Patent 4933 on 27 November 1880.[10] From that time he began installing light bulbs in homes and landmarks in England.

Today, lighting choices have expanded and people can choose different types of light bulbs.

The story of the light bulb begins long before Edison patented the first commercially successful bulb in 1879. In 1800, Italian inventor Alessandro Volta developed the first practical method of generating electricity, the voltaic pile. Made of alternating discs of zinc and copper - interspersed with layers of cardboards soaked in salt water - the pile conducted electricity when a copper wire was connected at either end. While actually a predecessor of the modern battery, Volta's glowing copper wire is also considered to be one of the earliest manifestations of incandescent lighting.

Not long after Volta presented his discovery of a continuous source of electricity to the Royal Society in London, an English inventor named Humphrey Davy produced the world's first electric lamp by connecting voltaic piles to charcoal electrodes. Davy's 1802 invention was known as an electric arc lamp, named for the bright arc of light emitted between its two carbon rods.

While Davy's arc lamp was certainly an improvement on Volta's stand-alone piles, it still wasn't a very practical source of lighting. This rudimentary lamp burned out quickly and was much too bright for use in a home or workspace. But the principles behind Davy's arc light were used throughout the 1800s in the development of many other electric lamps and bulbs.

In 1840, British scientist Warren de la Rue developed an efficiently designed light bulb using a coiled platinum filament in place of copper, but the high cost of platinum kept the bulb from becoming a commercial success. And in 1848, Englishman William Staite improved the longevity of conventional arc lamps by developing a clockwork mechanism that regulated the movement of the lamps' quick-to-erode carbon rods. But the cost of the batteries used to power Staite's lamps put a damper on the inventor's commercial ventures.

Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, was a British physicist and chemist. He is known as an independent early developer of a successful incandescent light bulb and is the person responsible for developing and supplying the electric lights used in the world's first homes and public buildings (Savoy Theatre in 1881) to be lit with electric light bulbs

In 1904 Swan was knighted by King Edward VII, awarded the Royal Society's Hughes Medal, and was made an honorary member of the Pharmaceutical Society. He had received the highest decoration in France, the Légion d'honneur, when he visited an international exhibition in Paris in 1881. The exhibition included exhibits of his inventions, and the city was lit with his electric lighting. Swan was the maternal grandfather of Christopher Morcom, Alan Turing's close friend and first love during their studies at the Sherborne boarding school.

In 1850, English chemist Joseph Swan solved the cost-effectiveness problem of previous inventors by developing a light bulb that used carbonized paper filaments in place of ones made of platinum. Like earlier renditions of the light bulb, Swan's filaments were placed in a vacuum tube to minimize their exposure to oxygen, extending their lifespan. Unfortunately for Swan, the vacuum pumps of his day were not efficient as they are now, and his first prototype for a cost-effective bulb never went to market.

While Swan waited for the development of quality vacuum pumps, an American inventor, Charles Francis Brush, was busy developing an electric arc lighting system that would eventually be adopted throughout the United States and Europe during the 1880s. While not truly a light bulb, Brush's lighting systems could be used wherever bright lights were needed — such as in streetlights and inside commercial buildings. To power his systems, Brush developed dynamos - or electric generators - similar to those used that would one day be used to power Edison's electric lamps.

In 1874, Canadian inventors Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans filed a patent for an electric lamp with different-sized carbon rods held between electrodes in a glass cylinder filled with nitrogen. The pair tried, unsuccessfully, to commercialize their lamps but eventually sold their patent to Edison in 1879.

Swan sued Edison for patent infringement, and the British courts ruled against Edison (as punishment, Edison had to make Swan a partner in his electric company). Even the U.S. Patent Office decided in 1883 that Edison’s patent was invalid, as it also duplicated the work of another American inventor.

As it happens, Swan and Edison worked from bulb designs that had been in use since the early 1800s. The general principle was, and still is, this: When electrical current flows through the bulb’s filament, the filament heats up and glows, which produces light. The inside of the bulb is a vacuum, hence oxygen-free, so the filament doesn’t get oxidized and the glow lasts a long time.

In 1850 Swan began working on a light bulb using carbonized paper filaments in an evacuated glass bulb. By 1860 he was able to demonstrate a working device, and obtained a British patent covering a partial vacuum, carbon filament incandescent lamp.[citation needed] However, the lack of a good vacuum and an adequate electric source resulted in an inefficient light bulb with a short lifetime.

In 1875 Swan returned to consider the problem of the light bulb with the aid of a better vacuum and a carbonized thread as a filament. The most significant feature of Swan's improved lamp was that there was little residual oxygen in the vacuum tube to ignite the filament, thus allowing the filament to glow almost white-hot without catching fire. However, his filament had low resistance, thus needing heavy copper wires to supply it.

Swan first publicly demonstrated his incandescent carbon lamp at a lecture for the Newcastle upon Tyne Chemical Society on 18 December 1878. However, after burning with a bright light for some minutes in his laboratory, the lamp broke down due to excessive current. On 17 January 1879 this lecture was successfully repeated with the lamp shown in actual operation; Swan had solved the problem of incandescent electric lighting by means of a vacuum lamp. On 3 February 1879 he publicly demonstrated a working lamp to an audience of over seven hundred people in the lecture theatre of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne, Sir William Armstrong presiding. Swan turned his attention to producing a better carbon filament and the means of attaching its ends. He devised a method of treating cotton to produce "parchment used thread" and obtained British Patent 4933 on 27 November 1880.[10] From that time he began installing light bulbs in homes and landmarks in England.

Today, lighting choices have expanded and people can choose different types of light bulbs.

No comments:

Post a Comment